Major Findings

the four main results

There are 2.9 billion fewer breeding birds in North America than there were in 1970.

Even common, beloved species have undergone staggering losses.

Landscapes are losing their ability to support bird populations.

Yet over this same period, landmark conservation efforts have helped bring some birds back.

what is new about this study?

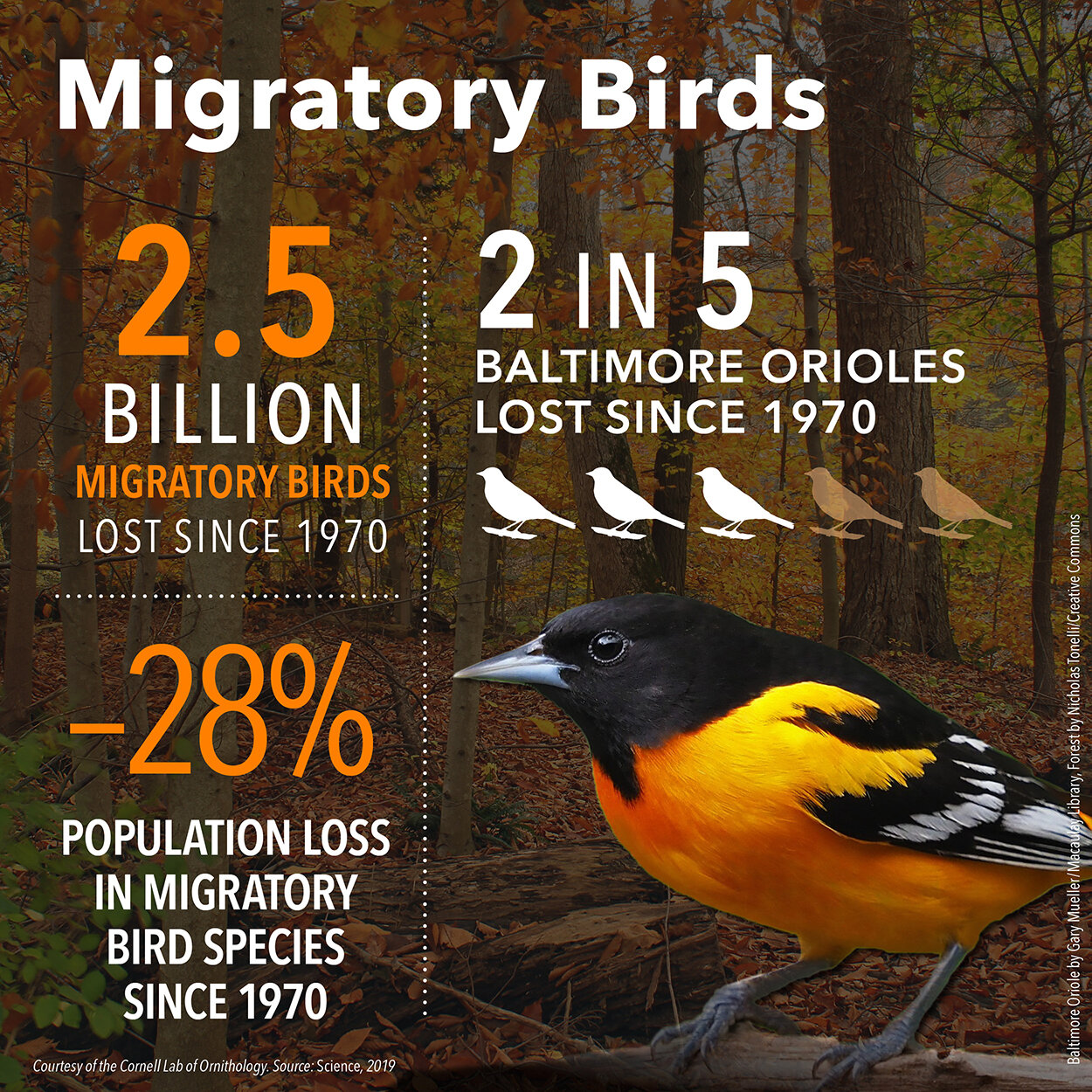

This is the first study to undertake an accounting of the net population changes across a total of 529 breeding bird species in the United States and Canada. The researchers analyzed birds on a group-by-group basis, allowing them to identify declines among species that use similar habitats. The data included 48 years of data from multiple independent sources, including the North American Breeding Bird Survey and the Christmas Bird Count. A comprehensive analysis of 11 years of data from 143 NEXRAD radar stations showed a similarly steep decline in the magnitude of migration.

The study clearly shows that the losses threaten some of our most common and beloved birds. Of the nearly 3 billion birds lost, 90% came from just 12 bird families, including sparrows, warblers, finches, and swallows. These common, widespread species play influential roles in ecosystems. If they’re in trouble, the wider web of life, including us, is in trouble.

is 2.9 billion a lot?

It’s huge: a net loss of 29% of the breeding bird population over the last half-century. This net loss takes into account both increases and decreases over the last half-century, like the bottom line on a bank statement. Each year, many birds produce young while many others die. But since 1970, on balance, many more birds have died than have survived, resulting in 2.9 billion fewer breeding birds today—that’s a loss of more than 1 in 4 birds that were alive in 1970.

“We were astounded by this result of a net loss across all birds on the continent. The numbers are staggering.—study author Ken Rosenberg”

where are the worst LossES?

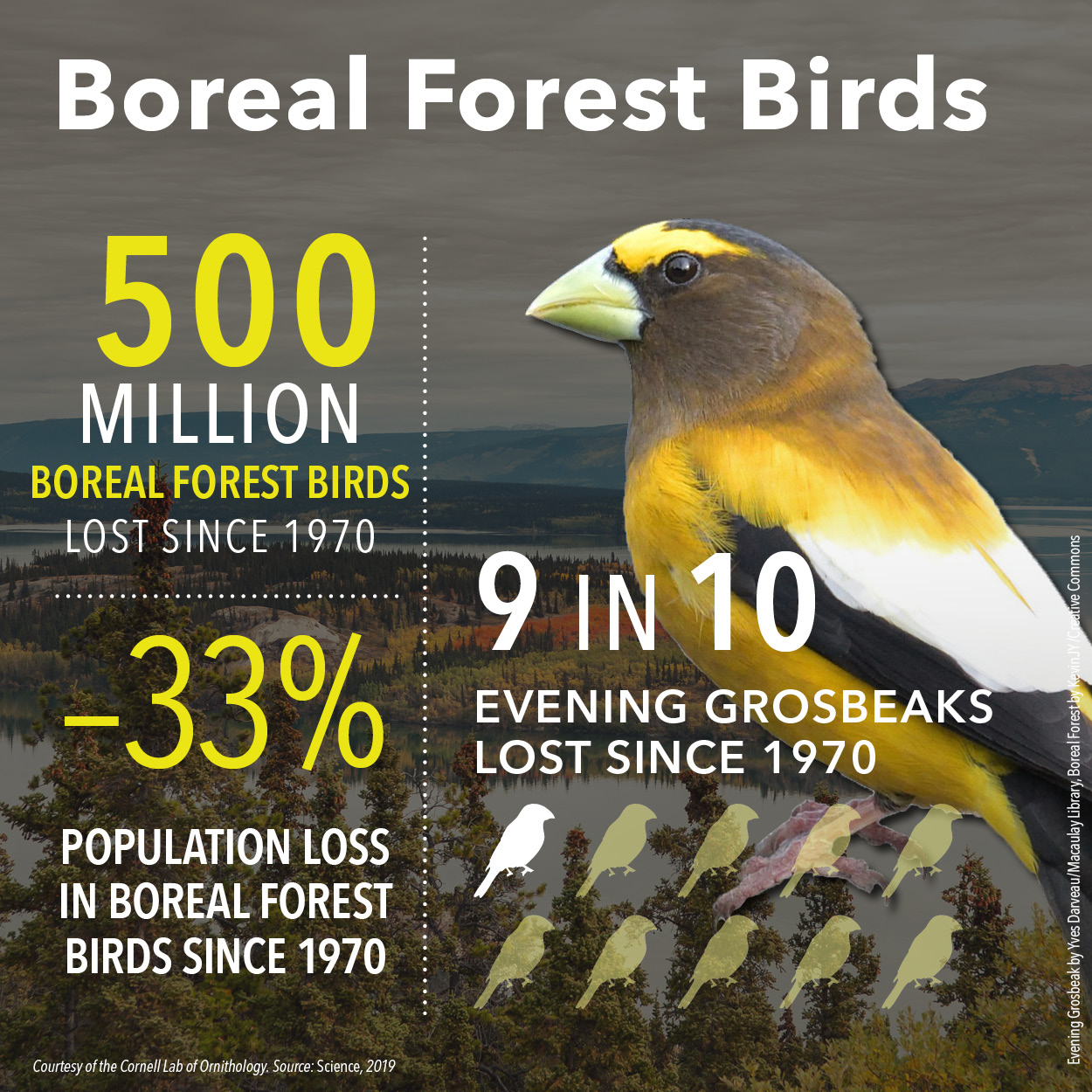

Forests alone have lost 1 billion birds since 1970.

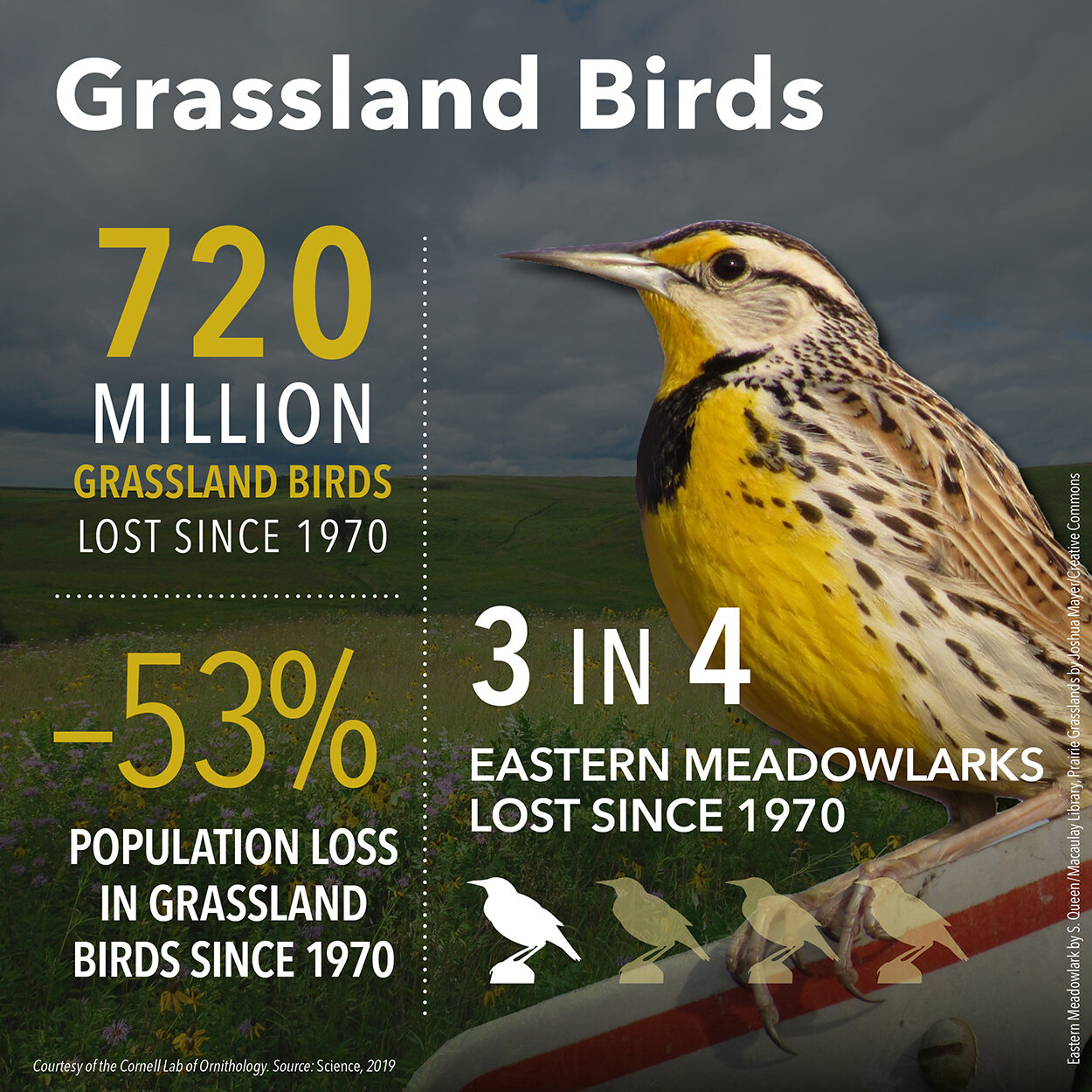

Grassland birds are also hard hit, with a 53% reduction in population—more than 720 million birds.

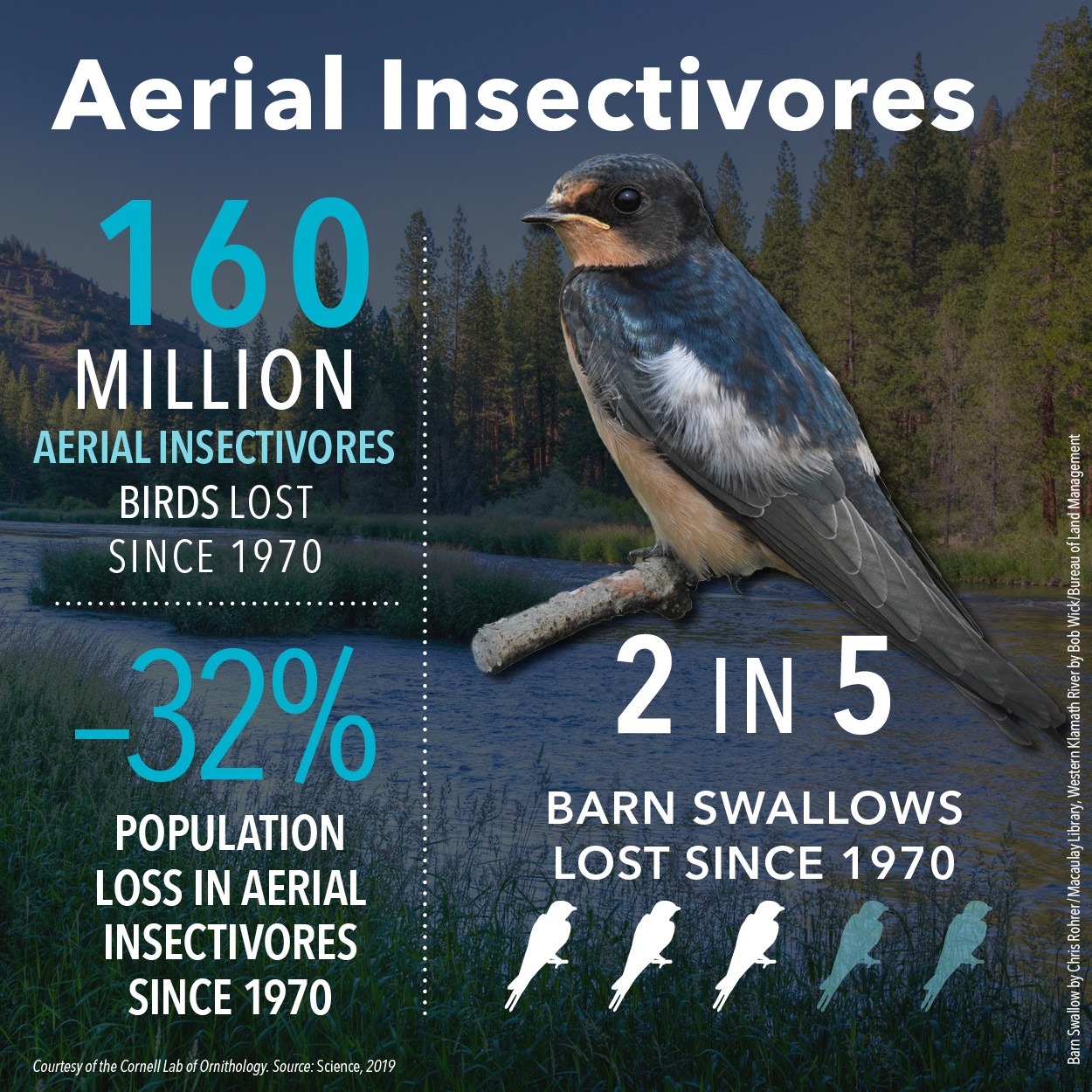

Aerial insectivores—birds like swallows, nighthawks, and flycatchers—are down by 32%, or 160 million.

Coastal shorebirds, already at dangerously low numbers, lost more than one-third of their population.

The volume of spring migration, measured by radar in the night skies, has dropped by 14% in just the past decade.

Habitat loss is the major driver of bird declines. Photo by Emily Guerin, used with permission.

What’s causing the Losses?

Although the study did not investigate causes, scientists have identified that habitat loss is the biggest overall driver of bird declines. When habitat disappears, all the birds that live there lose their homes. Habitat loss occurs when land is converted for agriculture, development, resource extraction, and other uses. Habitat degradation is a second cause of losses. In this case, habitat doesn’t disappear outright but becomes less able to support birds, such as when habitat is fragmented, altered by invasive plants, or when water quality is compromised.

Estimates of annual bird deaths from specific human-related causes (other than habitat loss) in the United States and Canada. Industrial collisions include deaths from power lines (57 million), communication towers (6.8 million), and wind turbines (140,000–679,089). Source: Loss et al. 2015.

Aside from habitat loss and degradation, other human-caused threats to birds come from cats, window collisions, vehicles, power lines, communication towers, and wind turbines.

Some threats are difficult to put numbers to: pesticides harm birds both directly (through poisoning) and indirectly (by reducing their food supply), but there’s no firm number for their toll in North America. (One study estimated 2.7 million bird deaths in Canada alone.) Likewise, there’s no clear estimate for the number of birds harmed by the burning of fossil fuels and the warming of our climate.

Yet many of the causes shown in the graph are ones where small individual actions can make a big difference—efforts like keeping cats indoors and making windows safer. Find out more:

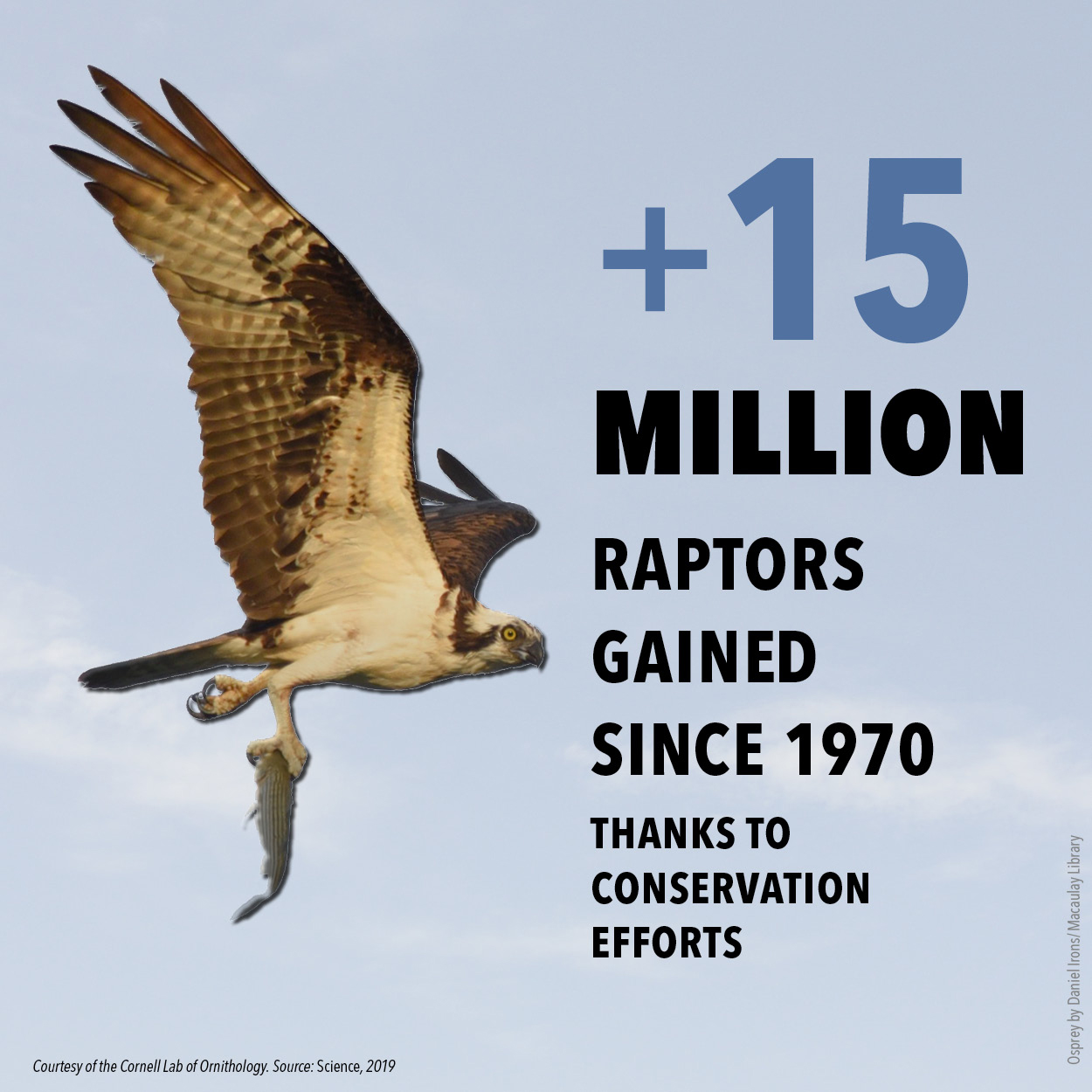

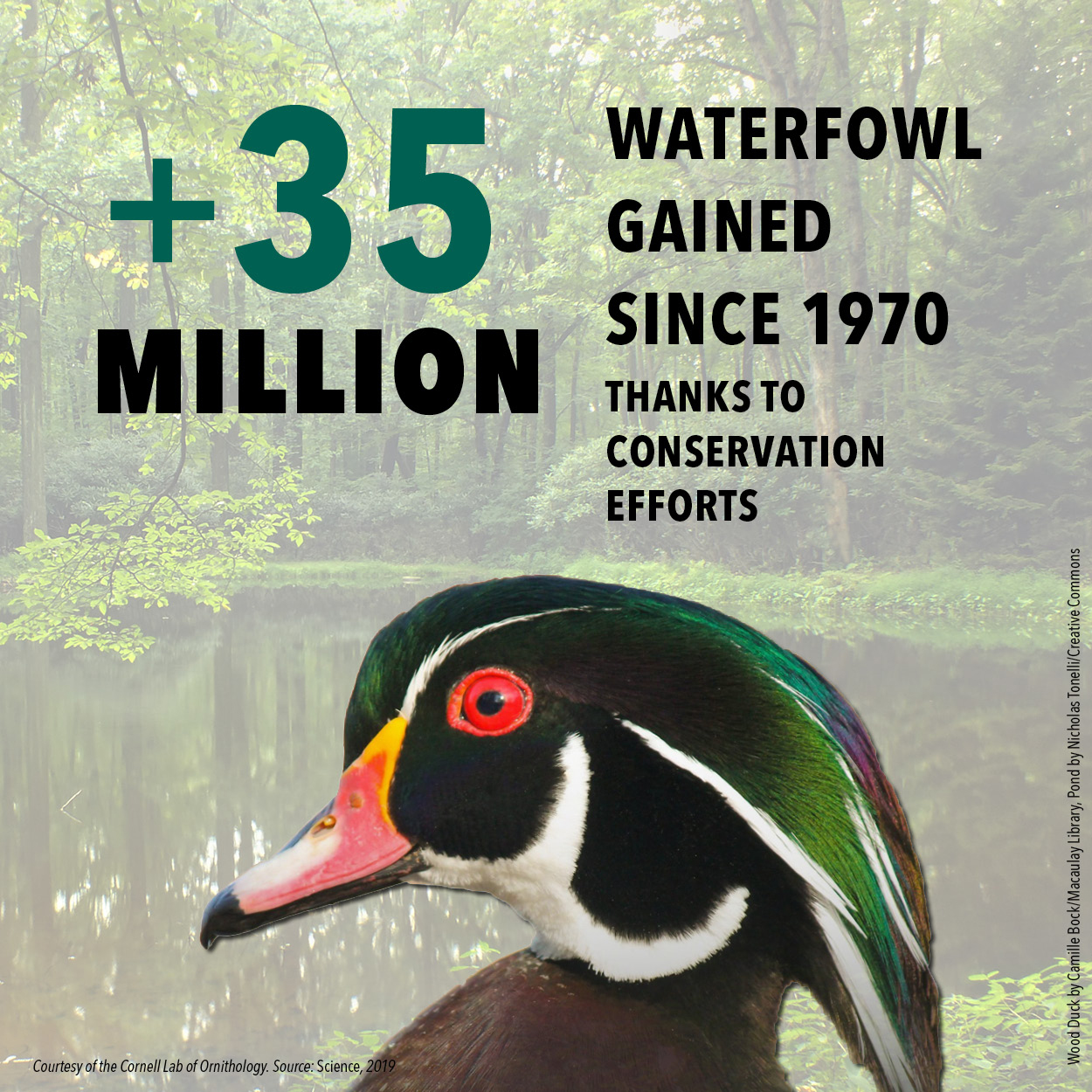

COMEBACKS: REASONS FOR HOPE

Birds are resilient, and they can rebound. Even while these widespread declines were happening, some bird groups have made rapid turnarounds—proving that concerted action can bring birds back. After the Endangered Species Act became law in 1973, vanishing raptors such as Bald Eagles, Peregrine Falcons, and Ospreys returned to the skies. When hunters and conservationists teamed up to restore the continent’s “duck factory” wetlands, dwindling waterfowl populations returned to vibrant health.

Waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans) have increased by 56 percent over the past 50 years.

This remarkable recovery has been made possible by conservation investments by hunters and billions of dollars of government funding for wetland protection and restoration.

The hawk and eagle family has increased by 78 percent, and Osprey populations have more than quadrupled.

Raptors such as the Bald Eagle have made spectacular comebacks since the 1970s after the harmful pesticide DDT was banned and recovery efforts through endangered species legislation in the United States and Canada provided critical protection.

The bottom line: Saving birds must start with all of us working together to mobilize the political will, funding, science, and conservation partnerships needed for birds across the Americas.

“We have models for success, but we’re lacking resources. We as a country need to decide whether we’re going to invest in the conservation of our ecosystems. —study author Arvind Panjabi”

ABOUT THE STUDY

Citation: Rosenberg, K. V. et al. 2019. Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 365(6461). doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1313

Reporters: To obtain a copy of the paper, please contact the Science press package team at 202-326-6440 or scipak@aaas.org.

Contributors: Cornell Lab of Ornithology, American Bird Conservancy, Environment and Climate Change Canada, U.S. Geological Survey, Bird Conservatory of the Rockies, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, Georgetown University.

Data were contributed by citizen-science participants in the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, Breeding Bird Survey, and other bird-monitoring initiatives. The Partners in Flight Avian Conservation Assessment Database was a critical source for the data.